A year of anticipation, and here I am in the land of rain and eternal mist — Foggy Albion. I expected gloomy skies, dampness, and perhaps even local ghosts grinning from behind Gothic spires. But, damn it, the weather decided to play tricks: not a drop of rain, not a wisp of fog. The sun blazed like a mockery, turning my raincoat into an oven. York was calling me forward. An art exhibition I’d spent a year preparing for awaited me there. But somewhere beyond the horizon, a storm was already brewing. And I could feel it: the thriller wasn’t creeping in from the skies, but invisibly, right behind me.

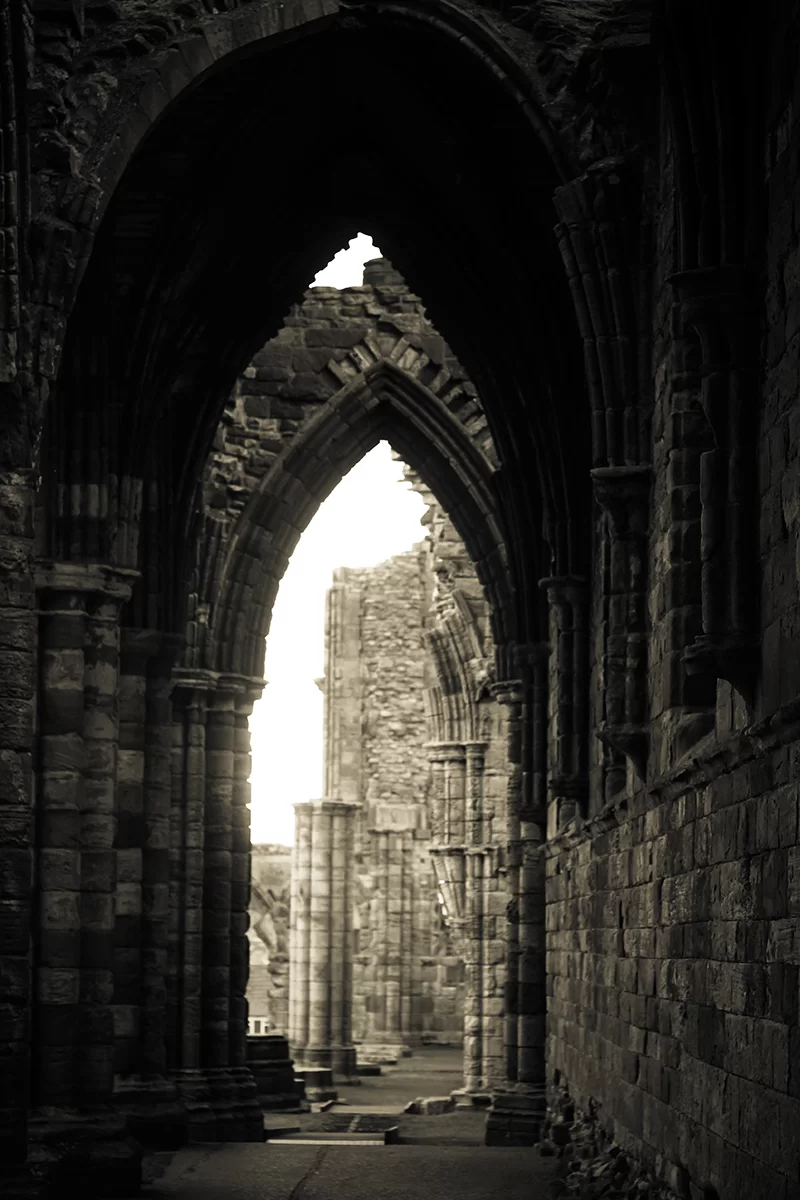

After crossing half of England, I found myself at its northern edge—where civilization fades into winds and wastelands. Beyond York, toward the cold borders of Scotland, stretched vast, rugged, almost otherworldly expanses. Endless carpets of heather, now yellow, now purple, rolled out to the horizon. At first glance, it was a postcard-perfect landscape, but an undercurrent of unease hung in the air. The dampness seeped into my bones, the sky often darkened with black clouds. And to the north, rising above the moors, loomed the ruins of an abbey—grim, like the exposed bones of the earth. They say it was those ruins that inspired the tale of Count Dracula.

York greeted me as one of England’s most enigmatic cities. Its gray stone walls held memories of Roman legions, Vikings, and knights. Narrow, crooked streets, like the gnarled branches of an ancient oak, whispered of days when the city was the king of the north. Time seemed to stand still here, save for the throngs of tourists bustling until late evening. Above the clamor and quaint medieval buildings, York Minster towered like a colossal stone giant. In the Middle Ages, it must have struck awe into the locals, dwarfing their humble hovels. Its spires pierced the sky, its stained glass scattered light into visions of crimson and emerald, and its gargoyles glared down at the crowds below, like vultures eyeing prey.

York was a place where time grew thin, where the line between the living and the forgotten blurred. At night, when the tourists’ daytime frenzy settled like a sea after a storm, the city transformed. Streets, alive with noise by day, now fell silent. I wandered, trying to lose myself in its magic, but a faint shadow of the moors seemed to trail me. A creeping unease stirred beneath my skin, as if the air trembled with an invisible threat.

I climbed the hill where William the Conqueror’s keep stood. The fortress, once a symbol of Norman power, was deemed impregnable for centuries. Yet it was here, in the 12th century, that a tragedy unfolded—the most brutal pogrom in medieval England. The city’s Jewish community, fleeing a mob, sought refuge behind these walls. As the rebels laid siege, despair outstripped hope. Men, women, and children chose death, doubting rescue would come. The stones remember them, and the silence here feels heavier.

The sunset bathed the city in blood-red light. Above York, clouds gathered swiftly—heavy, leaden, almost black. They loomed, pressing down on me. The air thickened with damp cold, and the sharp, metallic scent of an approaching storm warned that the sky was about to split.

Then it hit me—this was no ordinary storm. The city held its breath, the stones waited, and I waited with them. Dread pulsed beneath my skin. Something was coming—unknown, unstoppable.

From early morning, I felt the full might of the Minster. Bell-ringers climbed the spiral staircases and, as if possessed, struck the bells. They paused briefly—then the brazen tolling spilled over the city again, mingling with the aroma of fresh buns from bakeries, purple wisteria, and the damp wind off the River Ouse.

The 17th-century house where I temporarily settled held a peculiar silence and the spirit of antiquity. Worn furniture, as if soaked with others’ stories, a bust of Apollo on the windowsill gazing through a cluster of melted candles, white walls, and creaking floorboards that responded to every step—all of it evoked scenes from Wuthering Heights. It felt as though the house remembered those who lived here before me.

No less astonishing was how I ended up in this story at all. A complete stranger, a woman from England, stumbled across one of my paintings online. She was so taken by it that she reached out. Things moved quickly: she offered to sponsor me, invited me to move to the UK, and later arranged an exhibition in York. It was like magic—I hadn’t told anyone that living in Britain was my dream.

Everything was going perfectly. The paintings were due to arrive any minute. But the strange foreboding from yesterday wouldn’t leave me. I decided to check the tracking. And, my God—they were still in Germany. No one had even shipped them.

The grim premonition that had haunted me the day before became reality. From that moment, one of the most dreadful bureaucratic quests of my life began. But back then, I knew nothing yet. Naively, I thought it was a minor glitch, that the paintings would arrive soon, the exhibition would go on, and afterward, I’d travel around Britain.

I called DHL. And heard:

“We sent them… somewhere. The paintings are somewhere in Germany.”

Soon, it became clear: no one had even planned to ship them. The Germans had sent them back and told me to urgently return for them. Only no one knew where exactly they were. Return home? What madness! I’d spent so much time and money getting here, the exhibition was about to open—and now they tell me there’s no shipment. Just a “system error.”

I realized everything was falling apart. My paintings, each a product of months of work, the result of effort and poured energy—gone. Every brushstroke, every detail that took hours, days, nights—vanished in the absurdity of German bureaucracy. I felt everything I’d created over a year collapsing in an instant, and a sense of powerlessness gnawed at me from within. My exhibition was turning into a nightmare. Germany, curse it, had plunged me into hell: the entire series was lost. Instead of an exhibition, I found myself in a convoluted detective story with an absurd ending. The crates with my canvases had dissolved into the system, and now I had to unravel it—without the slightest idea how it would end.

The next morning, I received an email from DHL. The words were dry as autumn leaves but sharp as a knife: “Your paintings could not be found.” The loss of an entire series of works, each brushstroke a piece of my soul, turned the anticipated exhibition into a nightmare. York, which had enchanted me with its magic just yesterday, now felt like a labyrinth where I was forced to search for answers.

And then the real catastrophe began. Someone at DHL, as if snapping awake, decided to finally ship the paintings. But what followed was an endless maze of calls, emails, and paperwork. Every action only tangled the situation further. The bureaucratic machine chewed up documents, lost them, then found them, only to drown them in chaos again. It felt like I wasn’t speaking to people but to shadows behind the walls of endless offices. In the end, everything blurred into confusion: no one knew when the paintings would arrive—or, worse, where they were headed. This wasn’t just bureaucracy—it was absurdity come to life, playing an endless game with me where the rules changed every minute.

After hours of battling German bureaucracy, I needed to pull myself together. I set out to wander York’s nighttime streets. As dusk fell, the city’s peculiar magic returned. At this hour, the boundary between reality and the whispers of shadows dissolved.

York is a maze of narrow streets, and legend has it many are teeming with ghosts. Though, among them, you’d also find more earthly sights: rainbow flags, ghost-like cats in shop windows, and figurines of busty women, whose shapes were anything but ethereal.

Shambles, with its leaning houses where upper floors nearly touched, felt like a place where a cloak might vanish around a corner or a secret passage could open. By day, it swarmed with tourists, but by evening, the street emptied, and the stones seemed to whisper, recalling old tales. The atmosphere was like a street of witches and wizards from Harry Potter. There was even a wand shop, though I never saw anyone fly out on a broomstick. I thought how brilliant it would be to create a VR tour, showing the city through different eras, populated by ghosts of the past.

In search of York’s spirit, I headed to its ancient pubs—where the pulse of Britain beats. Pint glasses clinked like abbey bells, conversations mingled with legends and laughter. Some pubs echoed with rock, others with old folk tunes.

A particular ghostly aura hung over The Golden Fleece. Wooden beams, narrow corridors, strange sounds… One of the city’s oldest inns, supposedly home to fifteen ghosts—almost like King’s The Shining. The owners could probably charge for a night with a specter. I didn’t spot any ghosts myself—guess they only show up on request. But the walls were adorned with white death masks, and at the bar, alongside the bartender, stood a skeleton with a canine skeleton companion. No surprise, considering the cellar once served as the city morgue.

The House of Trembling Madness, on the other hand, was a portal to medieval York. Behind heavy oak doors lay a world of knights, alchemists, and mages—a labyrinth of Gothic stained glass, dark wood, and ancient artifacts. Armor and dust-covered books hung on the walls, alongside animal heads with frozen gazes, like guardians of ritual secrets. They served beer brewed from ancient recipes—bitter, with a taste of forgotten times.

When I stepped out of The House of Trembling Madness, night had fully enveloped York. Even the Minster blurred into the night, transforming in the moonlight into a giant spirit of the city. Its spires clawed at the stars, and its stained glass glimmered like eyes full of secrets.

My paintings were still drowning in German bureaucratic hell, and the city, with its pubs and shadows, remained silent. But I felt clearly that York was watching me, waiting—would I uncover the truth or be lost in its labyrinth?

Time dragged on, and it became clear: the exhibition was falling apart. Yet, by some utterly mystical turn, the Germans finally got their act together—they sent the paintings to Britain. They were somewhere en route, but no one knew when they’d arrive. I gave up waiting and decided to explore Yorkshire and the neighboring counties.

My tour began with England’s most modern cities—Liverpool and Leeds—but the farther north I traveled, the deeper I sank into a realm of gothic desolation, bleak moors and ruins, where vampires could easily lurk.

Liverpool, like Leeds, was a collage of Victorian architecture and avant-garde styles. Buildings of varied geometry—some mirrored, others matte black—resembled a living canvas by Kazimir Malevich. Futuristic structures clashed with the classics. Over Liverpool hung the spirit of the industrial age, especially on the street where the Beatles began. Now a tourist mecca with murals and throngs of fans, it was once a grimy district reeking of smoke, beer, and dampness, with peeling signs, soot-stained bricks, and the hum of factory sirens. Narrow streets and tenement houses carried the scent of poverty and coal. Music wasn’t born here—it clawed its way out.

Echoes of that era lingered in the Liverpool accent—sharp, brutal, almost impenetrable. You’d sooner mistake it for a Celtic dialect than English.

Liverpool Cathedral was no delicate European gothic but a stone golem frozen on a hill. Its massive redstone body seemed to blaze in the midday heat, as if engulfed in flames. Instead of elegant windows, it had glowing stained-glass eyes and narrow slit-like embrasures that watched the surroundings. This wasn’t a temple but a citadel, ready to withstand an onslaught of pagan hordes.

On my way back to York, for contrast with modern Liverpool, I stopped at the Brontë sisters’ home near Leeds. Haworth was like a gateway to the 19th century: gas lamps flickered at dusk, and heather-scented mists curled over rooftops. Time stood still in the cold stone houses and Victorian pubs. All around were peat bogs, heather, wet moss, and a harsh, relentless wind. The house stood by an old graveyard, and the sisters drank water from its well, often going hungry. Fine rain, wind, gray skies, constant cold, and poverty—such “cheer” drove their brother mad, and they all died young. The house’s facade faced the moor—step outside, and you were in the world of Wuthering Heights or Jane Eyre.

I didn’t immediately notice that my smartphone was nearly dead. I thought the power bank would suffice, but it was inexplicably drained. In that moment, a memory of Toronto hit me: my phone died then too, leaving me stranded in the freezing night outside the city—no signal, no bearings, as if cast out of the world. It felt like a sign: time to cut the trip short.

Picture an early, misty morning in the English countryside. A narrow road winds through ancient hills, cloaked in moss and legends. The driver, a silent guide, steers through the fog, the car’s headlights catching glimpses of old stone walls draped in ivy and lone oaks whose branches seem to whisper echoes of Celtic tales.

After crossing Yorkshire’s harsh moors, I arrived in Whitby—a charming port town. By day, it was a sunny resort: houses with red-tiled roofs crowded along narrow streets sloping down to the harbor, scented with salt, fish, and wet wood. Fishermen mended nets, seagulls screeched over the pier, and tourists bustled along the promenade, munching fried cod and snapping photos of the lighthouse. Victorian architecture breathed coziness and antiquity, but I could already sense something lurking beneath the calm. On many rooftops, I noticed figurines of red demons. Even in daylight, they looked unsettling.

But at sunset, Whitby transformed. The sun dipped, painting the sky blood-red, and darkness gradually enveloped the town. The demon statues, mere decorations by day, now seemed to come alive, watching me from the roofs. Dark, rugged cliffs loomed around the town, with massive North Sea waves crashing against their base. A fog slowly descended.

Above it all stood the ruins of the abbey, like the black bones of an ancient giant, half-drowned in the mist as if sinking into an unseen sea. Nearby, among the foggy expanse, were islands of tilted gravestones, covered in moss and lichen. This place felt like a portal between worlds, a lair for Nosferatu. I was stepping into the pages of Bram Stoker’s famous novel. During a storm, a ship with a dead captain lashed to the wheel appeared in the harbor, and from its hold burst a monstrous half-dog, half-wolf that vanished into the night. It was here that Dracula, in the form of a black dog, leapt ashore and climbed the steps to St. Mary’s churchyard.

Yes, Bram Stoker had been here, and the abbey’s ruins so captivated him that they inspired the creation of his iconic vampire. Now, this place is a mecca for every vampire fan with plastic fangs.

The weather was rapidly worsening, so I hurried to continue north to Scotland. By then, the exhibition had completely fallen through, but the resolution to the painting delivery was drawing near.

Near the coast of Scotland, a half-sunken 18th-century frigate is discovered. Its hold engulfed the explorers in a thick, stifling darkness, steeped in salt and decay. Three researchers cautiously descended a rotting staircase, their flashlights catching only the rust of chains and fragments of decayed planks. They hoped for treasures: heaps of gold, relics of a colonial empire. But the hold was empty. The only hint of former value was a pair of golden shackles, carelessly tossed on the floor, glinting dully in the half-light like a sinister jest of fate.

One researcher, driven by an inexplicable urge, stepped toward a compartment. The door yielded with a long, groaning creak, and in that moment, reality shattered.

That researcher was me. I was no longer on the deck. Nor on Earth.

Around me stretched an alien, warped cosmos—full of spheres and dimensions beyond human perception. A desert sprawled endlessly, its silence chilling the soul. This was a necropolis, but not a human one: wreckage of colossal ships—frigates, caravels—littered the expanse, their masts rising miles into a nonexistent sky, propping up absolute void like ruins of a forgotten pantheon. The landscape resembled a waterless ocean floor: only dust swirled underfoot, and a white mist hung low, revealing ground that was deathly green, like a decomposing corpse.

I stood frozen, speechless. Terror blazed in my eyes, binding my body with invisible chains.

Time passed—minutes, or an eternity?—before I found the strength to move and stumbled toward the nearest wreck. This ship struck me with painful recognition: the same frigate, now resembling a gutted carcass, a gaping wound in its side oozing primal darkness. Inside was the familiar hold, the same compartment-cell. And there, it waited.

My heart pounded in a feverish rhythm. There, in the heart of that darkness, I saw them. My paintings. They were ravaged: canvases slashed as if by claws, paints scraped away. The packaging was in tatters, but on the filthy scraps of cardboard, the familiar DHL logo still lingered. I turned and fled. A specter gave chase—it became a whirlwind, a monstrous gale, white as death itself. The storm roared, tearing the web of sails, whipping dust into suffocating tornadoes. I broke into an open field, lungs burning, legs buckling.

Suddenly, a door materialized in the air—a portal to another world. Through it streamed the warm, beckoning light of our world.

Through the doorway, I glimpsed a dimly lit bus interior, and at that moment, as if on cue, my body jolted. I snapped my eyes open.

The Necropolis. It smelled of damp earth and ancient stone. I was passing Glasgow’s City of the Dead. Outside the bus window, black obelisks drifted by, their jagged shadows evoking the masts of ghostly ships. But then the city lights grew denser, pub signs flashed in the windows, laughter and music spilled out. I was gliding into the city of the living. There, a friend was already waiting to meet me.

My entire project with the paintings—everything I poured a year of time and effort into—was sinking like the Titanic.

The DHL tracking showed that the packages had finally reached Britain and… had supposedly been delivered to me.

Delivered? No, they’d simply vanished. DHL offered no further information. Digging into the details, I learned: if I didn’t retrieve the paintings within a couple of weeks, they’d either be sent back to Germany or destroyed.

Returning to York made no sense yet—the package still wasn’t there. I decided to finally meet my friend and take a break from the nightmare I’d been plunged into.

Serge and I had traveled all over Ukraine and India together. The scrapes we’d gotten into! One vivid memory was when we set out to explore a series of castles in Ukraine, but I completely lost track of time. That evening, finding myself in the ruins of an Austrian fort in the forest, I felt like I was in Angkor Wat: a lost city in the jungle, with waterfalls and a dark tunnel leading straight into the fort.

I barely made it out: my flashlight and phone were dead, and the only light came from my camera’s flash. When I finally found Serge in a nearby town, it was too late—no transport ran in such a backwater at night. There was nowhere to stay, not a soul on the streets, and the cold cut to the bone.

By a twist of fate, in Rivne, the regional capital, a train to Kyiv awaited us at one in the morning. But how to get there? At first glance, it seemed impossible. The last city bus passed by, and the driver confirmed: no more transport, and hitchhiking was a lost cause. We were utterly deflated, facing a night of freezing on the street in a less-than-ideal place.

Then a miracle happened. The driver recalled a business card he’d gotten ages ago from a private transport service that once ran through that town to Rivne. The company might have gone bust, or the number changed, but we took a chance and called. To our luck, the driver was on the road and could pick us up in half an hour. We made it to the train just in time.

Over countless trips, we’d had plenty of such adventures. Yet, somehow, they always turned out fine. The climax of my painting saga was near, and I clung to hope that I’d soon recover my work intact.

Glasgow was a wild mishmash of styles and eras, far outstripping Liverpool in its chaos. The contrasts were stark and everywhere: wide streets lined with modern glass skyscrapers, neon signs, and sleek cars stood alongside classic Victorian buildings like the Kelvingrove Museum and remnants of medieval architecture. Amid this grandeur loomed grim 19th-century brick factories and half-empty alleys still reeking of coal and machine oil.

Here, beauty and ugliness walked hand in hand: locals dressed haphazardly, drunken crowds staggered through the streets, many barely staying upright. Over this vivid scene drifts the distinct cadence of the Scottish accent and the Scots tongue, entwined with Glasgow’s recent aura as one of Europe’s most notorious cities. Don’t mess with the Celts.

Strolling with Serge, I asked him about Glasgow. A passing Scotswoman overheard and answered herself: “Aye, it’s fuckin’ ugly.”

The city was indeed alive and untamed, just like its people.

In Glasgow, amid this cold northern grit, there’s even a pocket of fiery Spanish Baroque—the Kelvingrove Museum. Its residents include Rubens, Degas, Titian, Rembrandt, Botticelli, Van Gogh, and Picasso. Their masterpieces share space with a vast collection of historical artifacts, natural history exhibits—and, true to Glasgow’s nature, a characteristic jumble of everything.

The most famous site was Glasgow’s Necropolis. It had already flickered through my dream. Everyone described it as the city’s most captivating place. Scenes from Batman were filmed here. By evening, it’s treacherous to wander: you could trip over countless tombs and ruins. More than 50,000 departed lie here—no kidding. A true city of the dead.

Here, symbolically, like the River Styx, a bridge stretches, dividing the city of the living from the city of the dead, with the ominous cathedral looming as a grim Cerberus guarding the threshold. Crossing the bridge, I entered a tidied-up cemetery. Someone had decided it was a “brilliant” idea to spruce it up, aligning many monuments in neat rows, like a shop window display.

Strolling through the Necropolis, I recalled a night when I found myself in an old German park. I still don’t know how I ended up there. A fine rain fell, and fog hung in the air. At first, it seemed like an ordinary park: a vast hill lined with an avenue of yew trees. The air was thick with the sharp scent of pine, promising peace and solitude. But soon, I noticed countless flickers of light scattered across the “park,” like stars fallen to earth. They shimmered in the distance, beckoning with their warmth. Yet something was off. The lights didn’t radiate comfort—their glow was cold, ghostly, like the eyes of predators watching from the dark.

I stepped closer, and the illusion of a park began to crumble. Their flickering resembled the lights of Tolkien’s Dead Marshes—the souls of the fallen. Looking closer, I realized: these were candles for the dead, surrounded by endless graves. This was no park but a cemetery. I had the eerie feeling I wasn’t alone. The wind blew, and the yew avenue swayed, as if stirred by the breath of a vast, black beast.

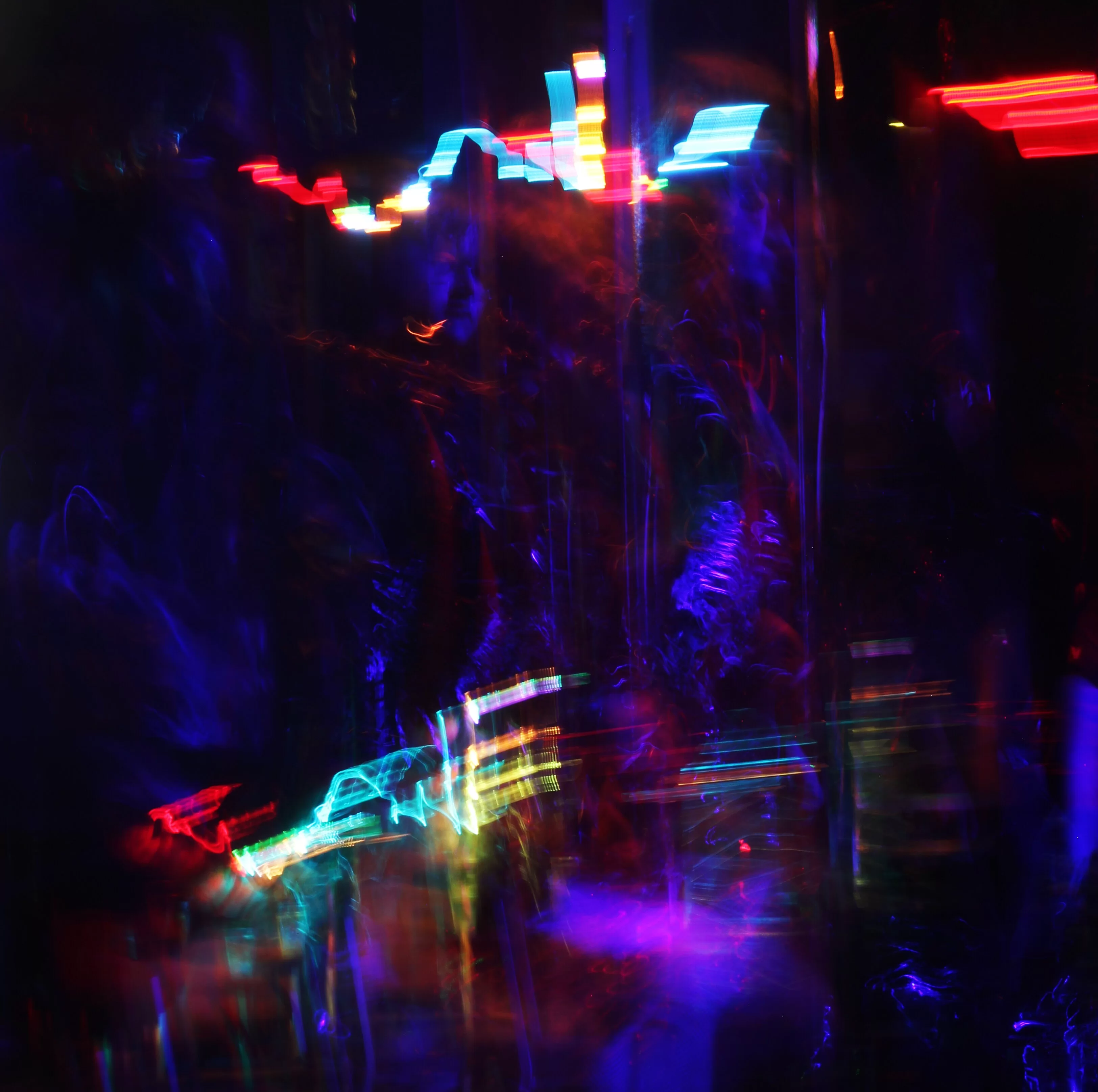

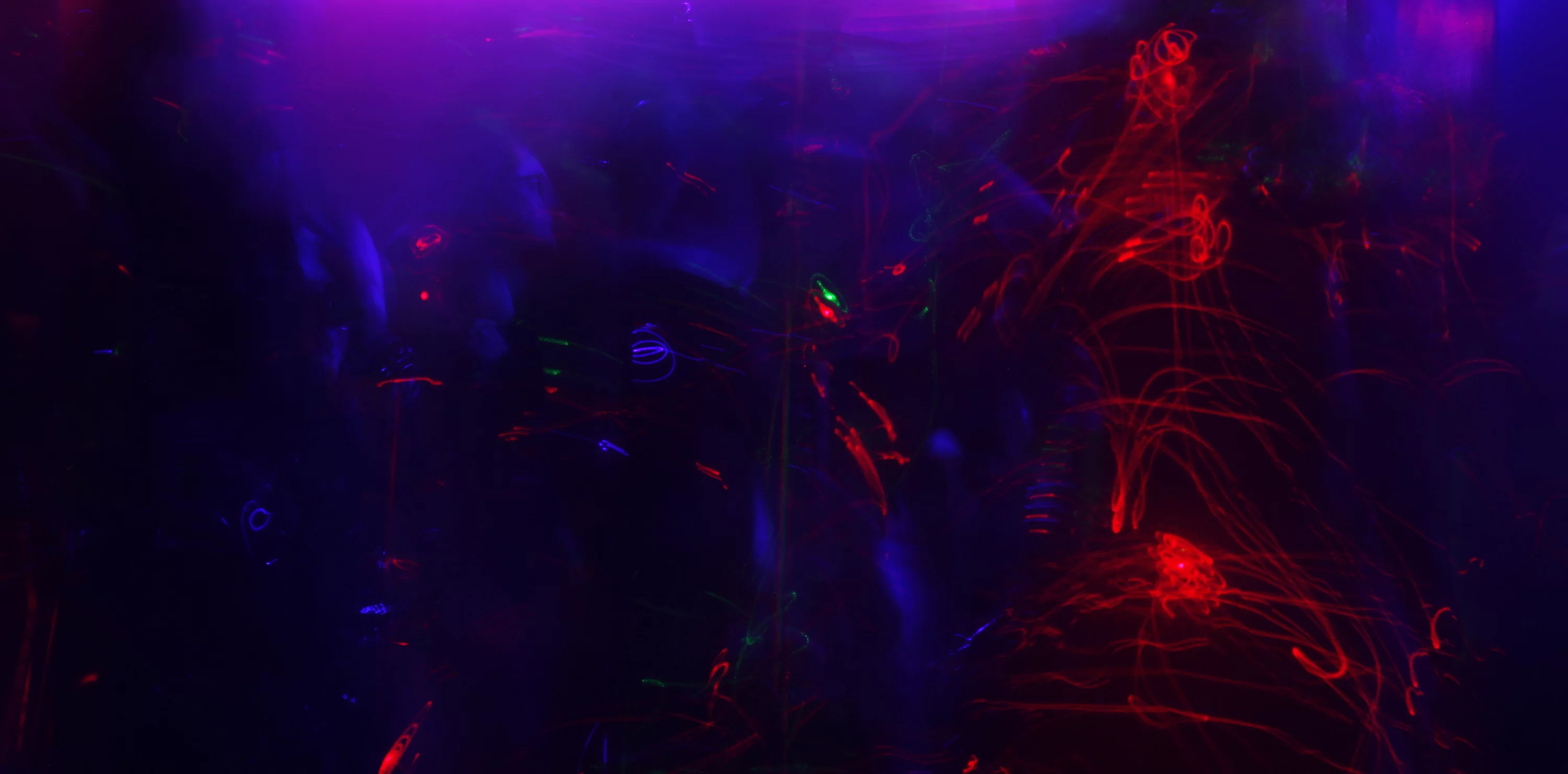

The gothic party was the crescendo of the surreal chaos that the saga of my missing paintings had dragged me into. At first, it seemed like an ordinary event: a DJ, a half-industrial building in Glasgow. The club was lit only by faint spotlights. Initially, it was quiet, almost deserted—as if the space itself had frozen.

Then a low rumble erupted, soon splintering into fragments, morphing into a pounding drumbeat. It grew and grew, as if a colossal creature were slowly clawing through the walls. That was the quality of the speakers: the music was barely audible—just bass, vibrating through every cell of my body. I felt the frenzied pulse of the rhythm in my veins.

The crowd swelled. The music grew fiercer. Serge danced with his girlfriend. I wanted to capture it in photos, but how? Colored spotlights shifted like an impressionist’s palette, but there was too little light for a clear shot. Faces dissolved: shapeless blurs, grotesquely distorted features.

Then it hit me: by lengthening the shutter speed, I could seize the madness of the moment. The photos came alive—wild, expressive, as if embodying the very energy of the space. Abstractions where almost nothing remained, only flecks of light—atoms, meteor streams, lasers pulsing to the music’s rhythm, reminiscent of Pollock’s paintings. In other shots, silhouettes of bodies, fragmented features—distorted, dynamic, like Bacon’s canvases, terrifying yet mesmerizing.

Everything around vanished except for a trembling golden glow. The world began to slip away; the light sources—powerful, radiant—seemed to emanate from within the beings themselves. My friends appeared to transcend the metaverse: fragmented into atoms, merging with infinity and eternity.

At least, in the photos.

I stepped out of the club, the drumbeat still thrumming in my veins. My phone flashed a message from DHL: “Your paintings…”—and the signal cut out. I knew: the surrealism wasn’t over yet.

Instead of an exhibition and rest—nothing but disappointment. I was utterly exhausted. Bureaucracy proved more terrifying than any graveyard or grim landscape. Reality drowned in chaos. But the paintings were a part of me. They had to be saved at any cost.

The final battle began—not with German delivery anymore, but with British. DHL had handed my work to a third party without even informing me, merely noting that the “package was received.” Later, I learned: another company had it and was waiting for payment. Payment? I’d paid everything upfront, and no new invoice had ever arrived.

When I sorted out the payment issue, the worst came to light—they’d entered the wrong address. The package label was correct, the tracking was correct, but their system stubbornly showed a different address. And the staff flat-out refused to fix it. The paintings had already been sent to someone else’s address.

I couldn’t believe such madness was possible. Everything hinged on strangers—whether they’d be home, whether they’d agree to hand over the documents needed to release the package. If they were away? It was all over.

My sponsor, Justine, in York saved me. She managed to secure the documents and retrieve the package. The packaging was completely torn, the works partially damaged—just like in my dream.

But hope dies last. I got the paintings back. And Justine even pulled off the exhibition. No one canceled it.

Time to go home. In London, amid the stress, an eye infection forced me to ditch my contact lenses. At the station, I could barely see—neither the schedules nor the bus numbers. Minutes remained until the airport bus departed, and I didn’t even know where its stop was. Stepping out of the station, I saw my bus pull up right in front of me.

The dreadful trip was over. But the paintings shone at the exhibition, and that made it all worthwhile.